Yellowstone National Park: Reconnecting with a Living Planet

“We have replaced the wild with the tame. We regard the Earth as our planet, run by humankind for humankind. There is little left for the rest of the living world. The truly wild world–that non-human world–has gone. We have overrun the Earth.”

– David Attenborough

Camp and Camera Gear in Yellowstone

Jess and I recently returned from a camping trip to Yellowstone National Park. We spent a week exploring, 5 days camping at Madison Campground within the National Park—a great basecamp. And 2 nights at Yellowstone Village Inn, in Gardiner, Montana, just north of the park—a hotel to recoup and shower! October’s Fall weather was perfect during the day, in the 60’s and 70’s, however it was below freezing at night, rather frigid! Camping and the fluctuation of weather urged us to adapt quickly to this new environment.

We went into Yellowstone hoping to find wildlife and just relax, but upon leaving I discovered the most important reason to visit Yellowstone National Park—to reconnect with a living planet that’s full of wildlife and balance, and to bring that knowledge back home to our decaying urban environments.

A night at camp. The October sun sets earlier, bringing with it an immediate chill. Most nights were below freezing; here Jess sits with the fire, dreaming of toastier times.

Nikon Z8 with the rented telephoto on the left. Fujifilm X-T5 on the right, my typical wildlife setup.

For the trip, I rented a telephoto lens, the Nikon Nikkor 100-400mm (a lens as big as its name) for my Nikon Z8. This would be the first time using this camera and lens for wildlife photography. The zoom range would help me get closer to larger wildlife without having to interrupt their flow, and it would help me blend with the environment, without it being too incredibly cumbersome. The camping gear included sleeping bags rated for 24°, a hatchet, water, coffee, tons of snacks, and a 3-person tent. Over the journey we hiked over 40 miles while exploring various locations such as the staples: Old Faithful, Grand Prismatic Spring, Geyser Basin, Hayden Valley, Mammoth Hot Springs, Yellowstone Lake, and Lamar Valley.

When I photograph I try to be as present and observant as possible, yet the reality of bringing a large piece of technology into nature dividing your face and the animal, is inherently disruptive. I find the less equipment I bring the more present I can be; the same applies to weddings, I do not want my mind to be on my equipment over moments. Jess on the other hand will sit and meditate while watching critters, a true observer! She is a psychotherapist and has no social media, nor does she flaunt her travels; rather, it seems she learns from her journeys, is restored by them, and can better show up for her clients as a result. Just speculating here! Anyways, she teaches me a lot!

Early Observations

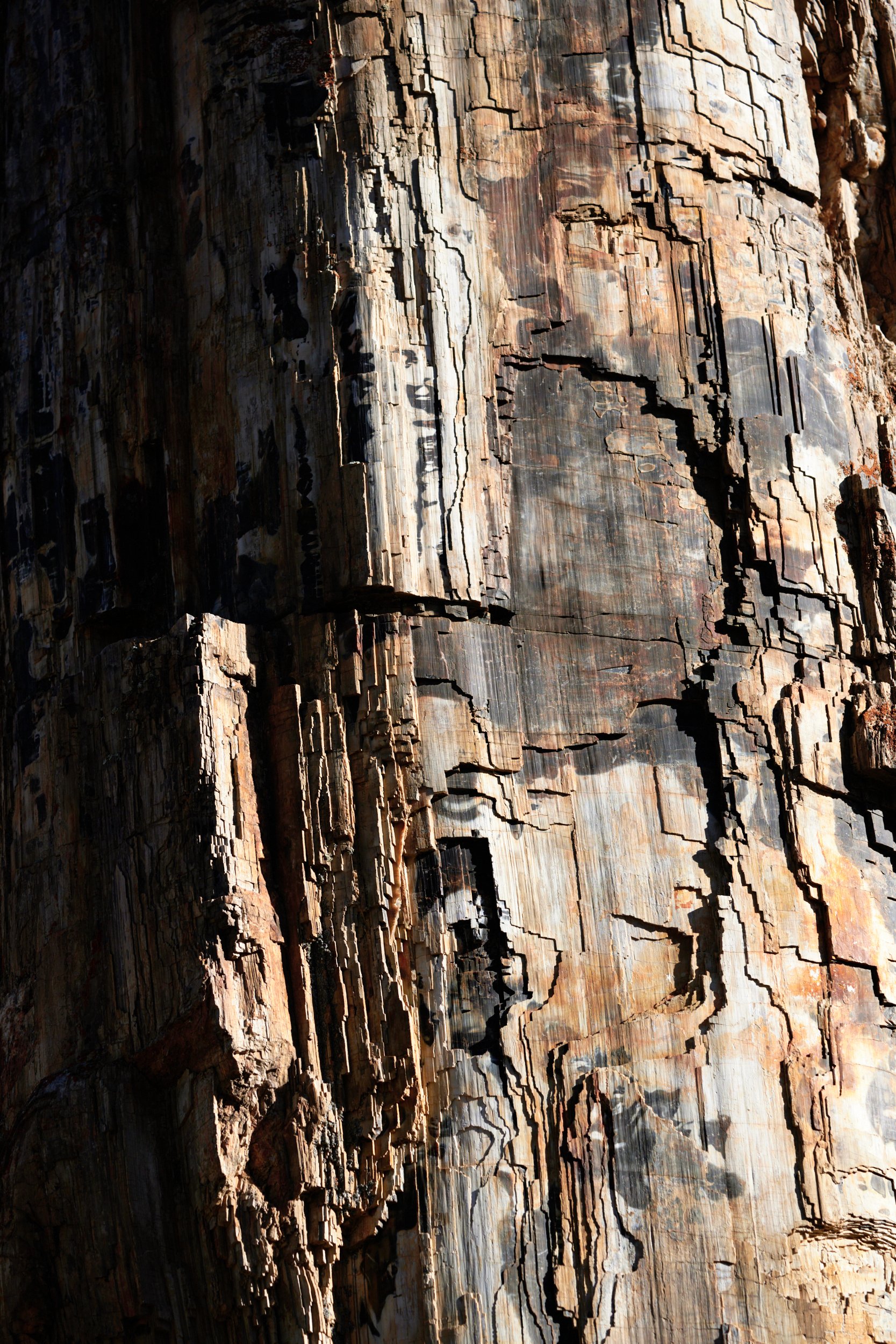

Seeing so much wildlife mixed into a dynamic volcanic landscape, perforated with bubbling hot springs, fumaroles, and geysers was uplifting in a way that I couldn’t describe until returning home. Camping really merged us with the danger of bears, wolves, and rutting elk. We quickly realized this was a danger we could bear. We weren’t worried about car accidents, break-ins, politics, shootings—rather we shifted our vigilance to those bears, elk, and wolves. But what felt dangerous at first became a beautiful blend of us with nature, like we somehow placed ourselves back into the ecosystem properly, where we got to be a part of it, even if that meant being a part of the food chain!

When a creature dies here, say a bison calf by a wolf, it provides so much life not just to the wolf pack, but to the bears, ravens, rodents, soil and grassland that then feeds the buffalo. As humans separate themselves from death and grief it seems we fear death more; it’s a natural cycle that we’ve removed ourselves from and it’s been interrupted and destroyed throughout the world. Age, too, is fended off with botox, plastic surgery, and photo filters. Today, when a “dangerous” animal wanders into an ever increasing urban population, they’re deemed a threat and killed. There is no room for more fear in a life that throws pure terror at us from social media and news.

An animal carcass continues to feed the grasslands. I believe this is an elk or buffalo calf, but not certain.

Yellowstone reminded me of my childhood in the late 80’s early 90’s, growing up on a ranch in remote Eastern Oregon, where I was often surrounded by animals that felt safer than circumstances, but still dangerous. Today, that ranch is a ghost town. It was nestled in a high desert valley in Eastern Oregon that my grandparents purchased after returning from WWII. They were who I refer to as “the last cowboys”. The wild animals that would roam the ranch included cougars, badgers, rattlesnakes, black widows, coyotes, and more. I often felt held in the howls from those coyotes. What would it be like to be in community with them? So one night in Yellowstone when the howls from the wolves swept through our campground, I felt an immense relief from built up anxiety, a coming home to the natural world.

Overlooking the Grand Canyon of Yellowstone, from Artist Point.

As kids, my cousin and I would journey out together on this ranch. Exploring hills, valleys, and burning cow pies that she claimed, “her ancestors used as fire starter”. My cousin’s grandmother moved from the Pine Ridge Oglala Sioux Reservation in South Dakota after attending a boarding school. I word this how the story is told to us, though I wonder how much of this was forced, and whether words like “attending” and “moving" are ways to forget a more painful past. Recently, President Biden apologized for the 150 years of systemic abuse of Indigenous children at boarding schools at the hands of the federal government, calling it “one of the most horrific chapters in American history” (Brewer, 2024). Being kids, my cousin and I didn’t understand this devastating history and we forged our new journey, merging with the landscape and enjoying stunning adventures full of imagination.

My brother and I visited the ranch in 2022 when I took the below photo. The ranch has lost a lot of green and trees near the farmhouse but you can see the remote valley the home sits within. The house can barely be seen in a small patch of trees to the right of center. My grandparents raised three kids out here and were completely self-sufficient.

McCoy Ranch in Ironside, Oregon. Yellowstone reminded me of growing up here surrounded by wildlife.

Upon our return from Yellowstone, I was quickly reminded of what’s missing in our day-to-day hustle in urban environments. Being immersed in the cacophony of howling wolves, rutting elk, buffalo grunts, rivers, and all that nature provides, was cleansing.

Our Time in Nature Has Been Reduced to a Brief Spectacle in Our National Parks

The wild holds a special place in my heart; I feel like I’m a part of it in a way that our culture doesn’t actively honor, condone, or allow us time for. My close relationship with the high desert animals from childhood transitioned to marine life when I joined the U.S. Coast Guard, where natural and human-made disasters were common. I began to see more devastation of nature while losing myself to that work. When I witnessed the largest oil spill in our history killing so much wildlife, millions of seabirds, a part of me died with them. Now, when I see the forest clear cut from the airplane, a part of me dies with that forest. I don’t think I can fully convey the heartache that afflicts my body when I witness these things. The pain of service and traumas to both nature and people have begun to affect me in ways I can no longer ignore or suppress.

Above: Morning at the Artists Paint Pots, Yellowstone National Park. Below: 1) Old Faithful Geyser 2) Mud Volcano 3) White Dome Geyser 4) Mud Volcano

The night we returned from Yellowstone, I was checking the news for the first time in a week and one of the articles was from the BBC, speaking to a report published by the World Wildlife Federation (WWF). The headline read: "Wildlife numbers fall by 73% in 50 years”, mostly due to habitat loss (Briggs, 2024).

The findings from the WWF “Living Planet Report 2024” mention that, “habitat loss and degradation, driven primarily by our food system, is the most reported threat to wildlife populations around the world, followed by overexploitation, invasive species, and disease” (WWF, 2024). The urgency of this report coincides with what I’ve witnessed while piloting airplanes for wildfire and with time in the Coast Guard responding to disasters. I’m intimately familiar with this reality of habitat loss. From the sky, I see and realize how little wilderness is left—distances are made small by altitude and speed. National Parks feel infinite on foot, but are actually small specks in the vast landscape of human expansion and destruction. I do believe these natural spaces are important teachers still, in that they remind us of what life and nature can provide if we honor it. Of course Indigenous peoples didn’t need any reminding of this.

As Chief Luther Standing Bear, of the Teton Sioux said:

Kinship with all creatures of the earth, sky, and water was a real and active principle. In the animal and bird world there existed a brotherly feeling that kept the Lakota safe among them. And so close did some of the Lakotas come to their feathered and furred friends that in true brotherhood they spoke a common tongue. The animals had rights—the right of man’s protection, the right to live, the right to multiply, the right to freedom, and the right to man’s indebtedness—and in recognition of these rights the Lakota never enslaved an animal, and spared all life that was not needed for food and clothing. This concept of life and its relations was humanizing, and gave to the Lakota an abiding love. It filled his being with the joy and mystery of living; it gave him reverence for all life; it made a place for all things in the scheme of existence with equal importance to all (Nerburn, 1999).

Being in Yellowstone, surrounded by so much wildlife really hit that “73% loss of wildlife in 50 years” home. Outside of this park that was our reality. Yellowstone felt like a true refuge: what life could look like if we embraced the wildlife and let them thrive in their natural “chaotic” mess. Life outside that park reminded me of how we are turning urban life into a biological desert, a place where concrete, form, and safety rule.

What the Bison Teach

Buffalo taking an early morning stroll through Lamar Valley in Yellowstone.

Conservationist David Attenborough (you’ve likely heard his narration on nature documentaries) reflects on his life in his recent book, “A Life on Our Planet”. Here, he speaks of how he once viewed nature as abundant, but has since realized the significant devastation and species loss over time. He gives some startling statistics that have occurred in his lifetime which bring his urgency into perspective.

Notice the impact of population increase on remaining wilderness:

1937 World Population: 2.3 billion

Carbon in the atmosphere: 280 parts per million

Remaining Wilderness: 66%

———

2020 World Population: 7.8 billion

Carbon in atmosphere: 415 parts per million

Remaining Wilderness: 35%

Attenborough goes on to say:

Since the 1950s, on average, wild animal populations have more than halved. When I look back at my earlier films now, I realize that, although I felt I was out there in the wild, wandering through a pristine natural world, that was an illusion. Those forests and plains and seas were already emptying. Many of the larger animals were already rare. A shifting baseline has distorted our perception of all life on Earth. We have forgotten that once there were temperate forests that would take days to traverse, herds of bison that would take four hours to pass, and flocks of birds so vast and dense that they darkened the skies. Those things were normal only a few lifetimes ago. Not any more. We have become accustomed to an impoverished planet (2022).

Bison are a big part of Yellowstone’s ecosystem and were my main focus for photography. I love them. And I wish they still roamed free throughout the country. Buffalo populations in North America once numbered 30-60 million until they were slaughtered by white people as they worked to destroy a life source for many Indigenous people. By the time the mass extermination of bison was complete, the buffalo were nearly extinct with numbers as low as 1,000 (Atlas Obscura, 2011). Photos can be found with white people standing beside mountains of buffalo skulls, the prize of a sick culture.

Yellowstone is a place where 4 million park visitors a year can view and be with animals and they mirror to us what life once looked and felt like (National Parks Service, 2024). Even with that much human interaction, there is still a large population of wildlife that can exist and very few human deaths relative to that number. If we’re cautious and courteous, wildlife is not nearly the threat we imagine it to be. In Eugene, Oregon, (where I live,) a cougar or black bear will occasionally stroll too close to the city, wildlife “management” will kill the animal for encroaching upon “our” territory. As our cities and rural areas increasingly infect these wild spaces without incorporating other life, life will continue to be destroyed. As Attenborough says, “We have replaced the wild with the tame. We regard the Earth as our planet, run by humankind for humankind. There is little left for the rest of the living world. The truly wild world–that non-human world–has gone. We have overrun the Earth.”

To embrace the wild and reintegrate ourselves into nature is of the utmost priority and to visit places such as Yellowstone remind us of this—if we are observant—a trip to Yellowstone can be more than a spectacle, but rather a reminder of a way of life to honor again. Nature can remind us of the care we need to take for our collective future. There are solutions out there that include rewilding, planting native species, incorporating more natural spaces, wildlife corridors, etc., but to achieve these aims there needs to be a shift in culture, one where we can celebrate the success of the animal rather than our next purchase. I think the words by psychotherapist and author, Sharon Blackie, sum it up perfectly:

There is a collusive madness here, irrationality on a planetary scale. A civilization which can do this much damage to the planetary fabric on which it depends, and which can continue to do so in spite of unambiguous signs pointing to the catastrophic direction in which were heading, is nothing less than pathological. But our insanity springs from the fact that we have constructed an exclusively human world for ourselves, and in so doing, we have cut ourselves off from the source of our belonging: the land, and the non-human others who occupy it with us. We have lost touch with the sense which our ancestors had of being a part of the natural world, of living in our bodies, embracing the cycles of the seasons, fully present in time. We do not recognize ourselves any longer in their stories. Something essential has vanished from our consciousness. We are caught not only in an industrial wasteland, but in a Wasteland of the heart and the spirit. The Wasteland is not just outside of us, a sickness in the system, in our culture: the Wasteland is in ourselves (2019).

Thank you for joining. If you’d like to add your Yellowstone stories or reflections please leave them in the comments below.

Resources:

Blackie, Sharon. If Women Rose Rooted: A Life-Changing Journey to Authenticity and Belonging. September Publishing, 2019.

Brewer, Graham Lee, and Sejal Govindarao. “Native Americans Laud Biden for Historic Apology over Boarding Schools. They Want Action to Follow.” AP News, AP News, 26 Oct. 2024, apnews.com/article/indigenous-boarding-schools-biden-apology-reaction-666f5d55496a36bd0dc40a357714273e.

Briggs, Victoria Gill and Helen. “Nature Decline Is Now Nearing Dangerous Tipping Points, WWF Warns.” BBC News, BBC, 10 Oct. 2024, www.bbc.com/news/articles/c5y3j0vzpl3o.

Attenborough, David, and Jonnie Hughes. A Life on Our Planet: My Witness Statement and a Vision for the Future. Witness Books, 2022.

Nerburn, Kent. “Chapter 3: Ways of Learning.” The Wisdom of the Native Americans, New World Library, Novato, California, 1999, pp. 15–16.

“Visitation Statistics.” National Parks Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, www.nps.gov/yell/planyourvisit/visitationstats.htm. Accessed 13 Oct. 2024.

“Wichita Mountains Buffalo Herd.” Atlas Obscura, Atlas Obscura, 17 Aug. 2011, www.atlasobscura.com/places/wichita-mountains-buffalo-herd.

WWF (2024) Living Planet Report 2024 – A System in Peril. WWF, Gland, Switzerland.